Tuesday, September 8th, 1970 was the day I returned from the summer holidays to start my 6th-Form career at Maidstone Grammar School, and found myself for the third and last time with form-master Robin Traves in his wood cabin out in the MGS boondocks. Something happened that day that set the tone for the more laid-back year that was to follow. At the time, the funniest thing on TV other than the legendary ‘Monty Python’s Flying Circus’ was the American show ‘Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In’, in which host Dick Martin did an impersonation of a flounder by opening his eyes wide, turning his head to one side, and poking out his curled tongue. Brian Bangay and I loved it. On our first day, the earnest Mr Traves had us Germanists sit around his table while he gave us an RAF-style pep talk, on the lines of, “Gentlemen, it’s a privilege to have you back… done well to get here… tough challenges ahead… every man for himself… here to help”, and so on. It was going spiffingly until he added, “I’m sure you’re all man enough to cope. But don’t hesitate to approach me if anyone should flounder”. At that moment Bangay, who was sat opposite me, looked me in the eye and did a perfect Dick Martin flounder out of Robin’s sight. Having to stop myself laughing out loud was as tough as anything I’d have to face in the 6th Form. I feigned a coughing attack, and almost got a hernia trying to hold back the paroxysms of laughter. Somehow, Robin missed it all. Bangay, incidentally, was another funny man who’d turn into a successful headmaster; maybe an anarchic sense of humour is a prerequisite of running a school.

Brian Bangay (left) and Dick Martin, still working on their flounder impersonations.

I’d had to decide which three subjects I’d be taking for A-Level in nearly two years’ time. The obvious choice was to follow my neighbours Alan and Rob Neale in taking German, French and Latin; but I opted instead for English as my third subject – we weren’t allowed to take more – thinking it would be more fun in a much bigger class containing several friends. I also suspected that it would look better on my CV, the value of which was not clear to me but appeared important to contemporaries. It turned out a mistake. What I’d already discovered was that studying French and German meant a significant expenditure of time on French and German literature. The languages (essentially grammar and vocabulary) were dealt with within lessons and homework. Literature, however, meant heaps of extra reading to be done. I could just about live with A-Level literature in French and German, the works to be studied being relatively palatable plays, novellas and such. English, however, contrasted starkly and depressingly, being a hundred percent literature, and tedious stuff to boot. Milton looked like a trip to hell and back, and as for JM Synge’s ‘Playboy of the Western World’, I seriously wondered whether anyone would have given it a second glance if it had been written in Scouse or Cockney. After one term, I’d had enough, and decided to cut my losses before I spent the next eighteen months grinding through Thomas Hardy.

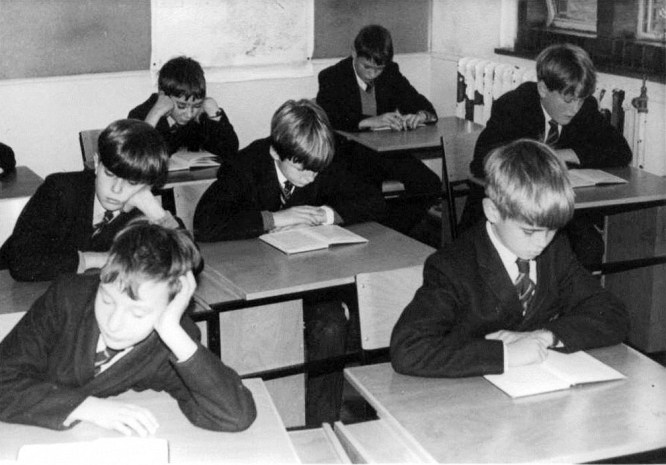

English A-Level: too much like hard work.

English A-Level: too much like hard work.

Tim Nicholls, of Ostend trip fame, was half the Latin set, and cajoled me into turning it into a threesome. Though not much of a linguist, he wanted to study History, and Roman history took up a third of the Latin course alongside language and literature. Nicholls swore by the history module, and he was darned right. I’ve never studied such a fascinating subject as Roman history from the Social War to the death of Marcus Aurelius, under ‘Killer’ Kemp. It even prompted me at seventeen to read in my spare time an entire history of Rome from 753BC to 476AD, which taught me more about humans in general and power politics in particular than anything I’ve ever done since. As time would tell, however, changing in midstream to Latin A-Level was a foolish decision academically. Consider that the third member of the set, Nick Mendes, was by then a contender for best Arts scholar in the school, found time for nothing but study, and had been studying Latin for thirteen terms, compared with my nine. Even he found it pretty heavy going. Mendes was as quiet as a church mouse, yet had a gentle sense of humour that revealed itself in a wry grin whenever he heard a flash of wit. It was this that set him apart from the average swot, though it escaped the teaching staff: I learned much later by accident that he’d been thought too introverted to make him a great candidate for Oxbridge. But I got on well with him. He even invited me to his modest home in central Maidstone so that we could spend time together doing original translations of Horace’s Odes, which had been baffling us. It sounds ludicrously dull; yet, when their literal meaning became clear, those poems came to life like budding roses.

Our highly agreeable French masters, ‘Vic’ Allen (left) and ‘Bill’ Nicholson.

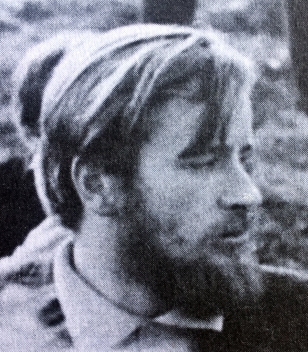

What otherwise helped make my sixth-form course in French and German palatable was the teachers; or most of them, anyway. For the former subject, we had two, TJ ‘Vic’ Allen and I ‘Bill’ Nicholson, who were easy to get on with. The latter was a bit dry but always interesting and pleasant, while the former was a treat to be looked forward to. By this time, we were tall enough to look our teachers in the eye, and the relationship became much more adult-to-adult than we’d experienced before. Vic’s approach, though rigorous enough, was to get us to learn through sheer enthusiasm, and that came as much as anything from shared laughter. Yet even he paled beside my favourite master, NAL ‘Spiny’ Norman. He had it all: handsome dark looks, quiet good humour, erudition and intellect, a perfect speaking voice, and the common touch in spades. He also hated politicians of all flavours with an absolute passion. Not long out of university, he plainly regarded us more as mates than pupils, and even invited us round to his home of an evening. What I particularly loved was studying Arthur Schnitzler with him: a Viennese Jewish contemporary of Freud whose stories were not only enthralling psychological thrillers but also had a teint of sexuality that made an exciting change from the usual fare. His classes actually made me feel that I was learning something useful, rather than just equipping me to pass an exam (which probably made me more likely to pass one).

Inspirational German-teacher Nigel ‘Spiny’ Norman looking busy in the language lab.

Inspirational German-teacher Nigel ‘Spiny’ Norman looking busy in the language lab.

In fact, after the pressure of the last eighteen months, the Lower Sixth felt like a chance to take a deep breath. It was a good time to do so, as society was settling down again after a period of intense change whose effects are still with us today. What we experienced of those great events was no more at MGS than the ripples of a distant storm arriving at an inlet; but the news was solid enough. It’s fair to say that the version of events that’s become standard today is removed by some distance from how things looked at the time. For starters, there was no great socialist revolution; even Daniel Cohn-Bendit, the figurehead of the Paris revolt, acknowledges that it was an utter waste of time. The Student Demonstration Time celebrated by the Beach Boys was more than anything an organised response to the Vietnam War. Though pitched as a revolt against American imperialism, to our cynical eyes it was actually the shenanigans of an army of young white middle-class males desperate to avoid conscription for the understandable reasons that (1) they preferred to stay home and participate in the free-love racket in which they could blackmail complete strangers into either having sex or facing the consequences of being branded “uncool”, and (2) they didn’t want to have their testicles shot off; see (1). The real political event of 1968 was in truth the Red Army’s crushing of the Prague Spring, when for the first time we saw with our own eyes what our parents and grandparents had meant when they said that, if someone tells you Communism is the New Jerusalem, you’d better run like hell.

Prague 1968: the Soviet Bloc displaying tolerance for everything but freedom.

Prague 1968: the Soviet Bloc displaying tolerance for everything but freedom.

What did occur after 1968 was a libertarian revolution: a great explosion of individualism (or selfishness, depending on your perspective) that killed off Victorian values for good. The best first-hand account I ever read on this was Paul Berman’s ‘A Tale of Two Utopias’, in which he describes from a hard-leftist’s perspective how an unlikely alliance of Women’s Lib, Black Panthers and the Gay Liberation Front commandeered socialist revolutionary tactics and rhetoric to facilitate an ambitious power grab. Social democracy it wasn’t. I suppose it’s inevitable that, when ideological theorising got so entangled with political expediency, we grew up thoroughly confused about the difference between liberal, libertarian, and leftist, even though their dictionary definitions made them mutually exclusive – a muddle that persists into the present day. I guess that, like everyone else, we just ended up cherry-picking the bits that suited us. We all loved the anti-establishment stuff, from Monty Python’s weekly ridicule of British institutions, via the outrageous flouting of moral standards spotlighted by the Oz obscenity trial, to the one-man revolt against the machine in Patrick McGoohan’s brilliant ‘The Prisoner’: “I am not a number! I am a free man!” We tried to do our bit in a small way, sporting fashionably subversive military-surplus trench-coats on the way to school, wearing tie-dyed vests beneath our white shirts, and sporting hair as long as headmaster Bernie Moody would let us get away with. I did push my luck with that last one, declining to back down until he eventually threatened not to sign my university application.

Patrick McGoohan of ‘The Prisoner’ fame: epitomised the spirit of rebellion.

Patrick McGoohan of ‘The Prisoner’ fame: epitomised the spirit of rebellion.

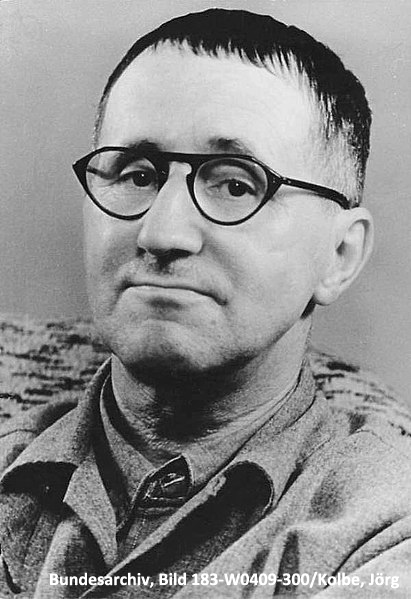

Bernie’s innate intransigence in this environment always made him look a Cnut trying to turn back the waves. His long-serving predecessor WA Claydon, a self-professed socialist, had left behind his legacy in the style of teachers he’d preferred to recruit. The curriculum and the pedagogical ethos were nothing like as polemical as I was to experience at university; but there was a definite tendency towards egalitarianism and iconoclasm in the 6th-Form Arts set that seemed satisfyingly in tune with the times. What was becoming more intrusive at the School was the trade-union militancy that would paralyse the nation in the 1970s. We had first-hand experience of it when the two main teachers’ unions, the National Union of Teachers (NUT) and the National Association of Schoolmasters (NAS), commenced industrial action over pay, albeit at odds with each other. Though its effect on our classroom activities at MGS was limited, it was a major talking-point nonetheless: I remember someone cheekily asking a teacher, “Sir, are you a NUT or a NAS?” and getting a serious answer. I didn’t know how much our teachers were taking home, but I was sure it was several times more than my father had earned on the factory floor or my mother on the wards, and the increases their teaching unions were now after sounded breathtaking. Meanwhile, staff permitting, I got on diligently with learning what the likes of Voltaire and Sartre, Kafka and Brecht had to say about the tangled web of human relations.

Marxist playwright Bertolt Brecht, who was to become a perennial subject of study.

Marxist playwright Bertolt Brecht, who was to become a perennial subject of study.

One moment on a Tuesday afternoon brought home to me the fact that, though opinions on national matters were pretty uniform across Shepway, not everyone else saw things the same way. Once a week throughout the 6th Form we would attend a two-period lecture in the Big Hall, no doubt meant to get us used to the concept before we went to university, as well as providing some handy pocket-money for the old buffers who came in to present them. They were all of general interest and, I suspect, intended to suggest some vocational options. Thus, for example, a police officer spoke fascinatingly about the forensic aspects of police work, though he spoilt it at the end by showing us pictures of a naked murder victim in a ditch; I was haunted for years afterwards by the spectacle of what maggots can do to a human head in the space of days. A Royal Navy officer gave a talk on the seafarer’s life, about which I remember nothing as well as I recall the Head Boy thanking him afterwards for an “admirable” lecture, which I thought rather witty from one of us. A less savoury occasion was a senior army officer’s enthusiastic account of some military escapade or other, which came across like one of the classic war stories we’d watched a dozen times in movies, but here recounted by an actual participant. When it came to question time, a boy rose to ask whether the speaker didn’t think this glorification of imperialism utterly shameful, and more of that ilk. The room froze. Apart from being surprised that any boy could have such chutzpah, I couldn’t help feeling for the old soldier, who’d grown up in a very different England from the one now emerging, and was plainly bewildered that not all these healthy young chaps were patriots like himself.

The fast-changing ‘Maidstonian’: Mr Palmer might have said it had become rather silly.

The fast-changing ‘Maidstonian’: Mr Palmer might have said it had become rather silly.

The truth is that, however enormous the advantages we enjoyed that had been denied to our parents, anti-establishment bias was embedded in the mindset of our generation. This was particularly true of the boys born a few years before us, the ones imbued with the true spirit of ’68 who sloganised endlessly from the comfort of their own incontradictability. Though often sceptical – I couldn’t help thinking that, compared with Britain, much of the world was woefully short on the Enlightenment values I was learning from Voltaire – I wasn’t always much different. When in our 5th Form a harmless bloke called Mr Pritchard had come in to promote the ‘Young Enterprise’ initiative to get us kids interested in commerce, I caused some hilarity by sarcastically rebranding it ‘Young Capitalists’. I didn’t understand then – as did even Lenin, Hitler and Deng Xiaoping, though not Mao or Pol Pot – that the state is handcuffed if it doesn’t allow at least some citizens to create wealth. In retrospect, many of us were more than a tad naïve, believing the West to be rotten to the core on the strength only of what our heroes of music, TV and film were telling us. It was taken as read that all change therefore represented progress. So change for change’s sake was everywhere. You even saw it in the ‘Maidstonian’, which morphed from its staid but solid format into something so ‘progressive’ that, in no time, it was even being lambasted from between its own covers, not least for the adolescent poetic and artistic utterances that made up its ‘Original Contributions’ pages. I for one, having never heard of evolutionarily stable states or strange attractors or phase transitions, didn’t appreciate that, if centuries of evolution have brought a people to any kind of plateau, no matter how low, the chances are that the only way is not up, but down. I don’t suppose many of us even suspected that, half a century on, our culture of carping and meddling would have led to the world about us: one where technological advance and material wealth are stupendous, but cultural coherence is largely lost, where the populace is fiercely divided against itself, and where even that Englishman’s birthright, freedom of speech, is increasingly outlawed.

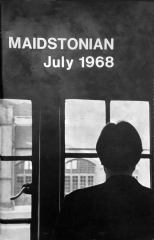

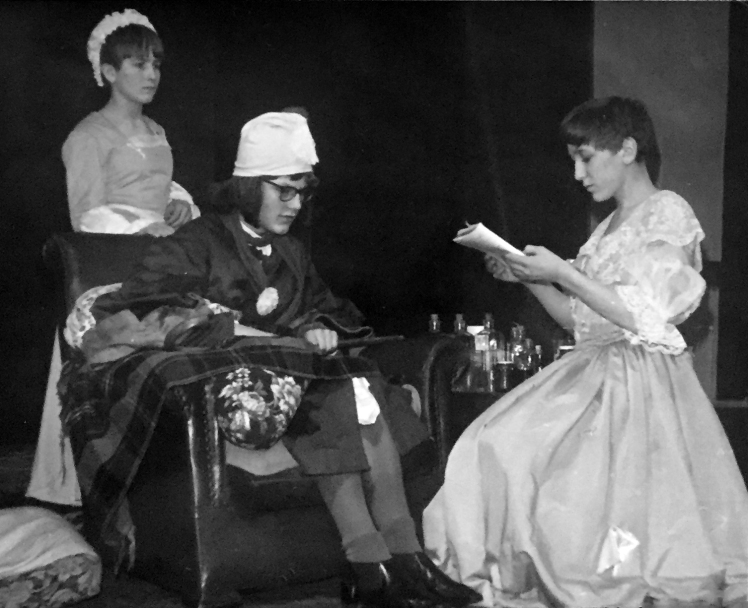

The 1966 Junior play ‘The Imaginary Invalid’: my first of countless experiences of theatre.

The 1966 Junior play ‘The Imaginary Invalid’: my first of countless experiences of theatre.

Yet, despite this sea-change about us, school life went on much as usual. I got to see a lot more of the Big Hall at this time. It was the main venue for screening the occasional random film, from the 1964 epic ‘Zulu’ to the 10-goal European Cup final of 1960 between Real Madrid and Eintracht Frankfurt. There was an evening of chat on the stage between a panel of football pundits that included future England manager Bobby Robson. The hall was also of course the school’s theatre, hosting an annual production that normally engaged me not at all, except when the Juniors staged Molière’s ‘The Imaginary Invalid’ and it was declared required viewing if we knew what was good for us. This was the first time I’d ever seen a proper play performed, but I can’t claim to have got much out of it, any more than when we were later taken en masse to see ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’ at the Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre. My mind was only changed in the 6th Form when Tony Mahony, who was playing Prince Escalus in ‘Romeo and Juliet’ in the Big Hall, persuaded me to serve as theatre usher. As a captive viewer obliged to pay attention to this co-production with the Girls’ Grammar, I was actually moved to tears, and for years afterwards became an addicted theatre-goer. The most curious cultural event however was a thoroughly arty-farty pot pourri organised by a former form-mate called Twigg, unforgettable for the moment when he introduced one of his own band’s songs with the words, “And now we’d like to play you a song from our new album”… and, yes, some doting soul had indeed let him record his own LP at seventeen. Twigg was the boy who, when Procul Harum’s new 1967 hit ‘A Whiter Shade of Pale’ was played to us in class, had breathlessly volunteered, “At first I thought it was Bach’s ‘Air On A G-String’, sir!” – which said to me as much about our divided world as it did about Twigg. Almost as toe-curling was a musical production of Handel’s ‘Feast of Alexander’ that took place shortly after I’d left. The School hired a professional soprano and tenor, but left the baritone part to our own Mr Nicholson, which was of course the reason I went back to watch. It wasn’t that ‘Bill’ couldn’t sing; the trouble was that, alongside the booming voices of the pros, it sounded like he’d been unplugged.

The Big Hall, where ‘Bill’ Nicholson gamely took on the pros – and lost.

The Big Hall, where ‘Bill’ Nicholson gamely took on the pros – and lost.

A major part of being a rebellious teenager back then was nailing your colours to the mast of the great new genre of music called rock; specifically, in my case, the ostensibly more cerebral branch called progressive or ‘prog’ rock, which Bangay had introduced me to via The Nice. Several of us being sub-prefects – note the modernised spelling by then – we would while away much of our spare time in our dedicated room on the ground floor of the old block, now the bursary, discussing the latest and forthcoming gigs. (It wasn’t until we became full prefects the following year that we could use the spacious Prefects’ Room at the top of the south-west staircase). For me, though, listening wasn’t enough. My upwardly mobile mother had bought a new bungalow up the Loose Road, a few doors along from Phil Baker. In between us, there lived an MGS 3rd-Former called Martin Woods who intriguingly owned an acoustic guitar. As he also had an old reed organ and a clapped out bass guitar, I ended up accompanying him, then writing lyrics for his songs, then singing them. At the age of sixteen, an absence of ability or experience seemed a bar to none of these. Before long we acquired the necessary drummer, followed by a keyboards player, followed by one or two proper instruments and amplifiers, whereupon we started having delusions of competence.

Martin Woods (far right) starts his MGS career, with future Head Boy Wynn behind him.

Martin Woods (far right) starts his MGS career, with future Head Boy Wynn behind him.

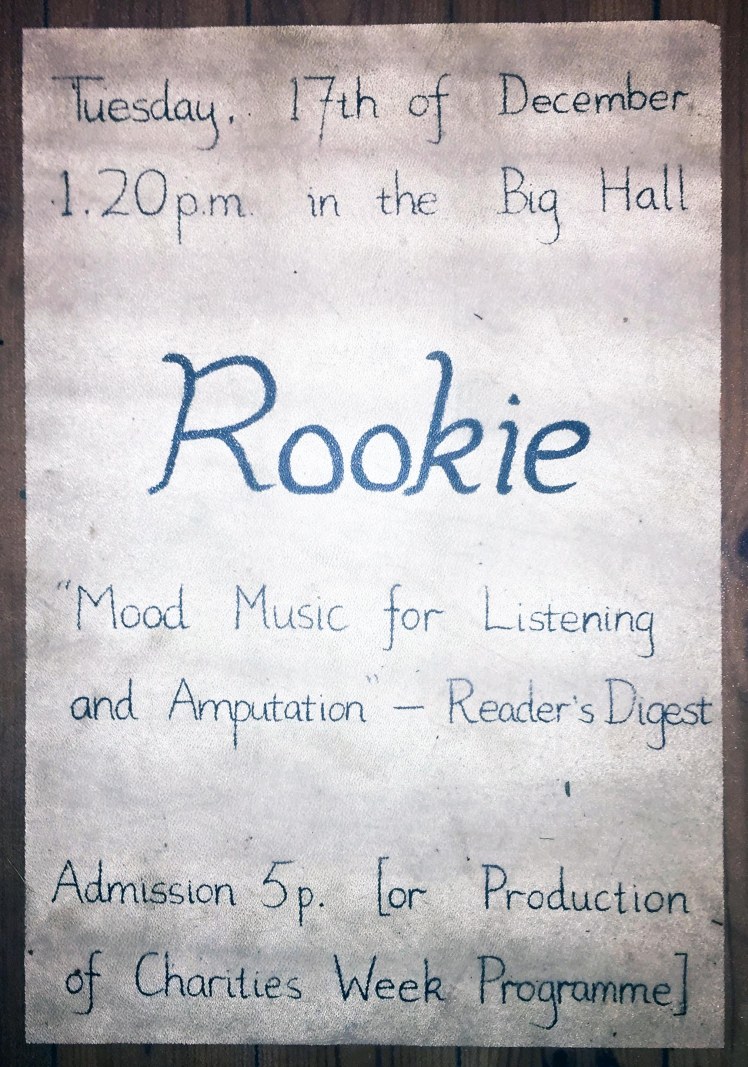

With Neil Sammells (another MGS boy and a future Gunsley Scholar at Oxford) helping out just the once on vocals, our first gig went well enough that we followed up with another in MGS’s Small Hall. Our name had changed by then from ‘Creeping Paralysis’ to ‘Brain Damage’, and it didn’t bode well when the poster announced that all proceeds were to go to Mencap. Suffice it to say that, without a proper lead-singer, we were dire. I summed it all up in my diary with a single word: “Disaster!” But mistakes are there to be learned from. We made good our shortcomings by securing a charismatic new vocalist and a PA system, leavening Woods’s compositions with some good ol’ rock-‘n’-roll, and practising harder. Our second gig at the school, this time in the Big Hall under our self-effacing and definitive name ‘Rookie’, was altogether better received by everyone but the teachers. We would go on to play together for seven years until work took us our separate ways. We even got so competent that a boy called Paul Featherstone got us to come into the Small Hall for a week during the holidays to help him record a rock opera he’d composed. Then Twigg said we might be of use to him as a backing band. How we laughed.

Rookie back at MGS: less painful the second time around.

Rookie back at MGS: less painful the second time around.

We five scions of MGS actually turned out such an eclectic bunch that someone suggested later we might have made for a decent TV documentary. Much the most conspicuously successful in later life was keyboards-player Kevin Loader, an unlikely rock musician insofar as he was incorrigibly posh and proper, possessing all the academic and social gifts to make him a shoo-in for Head Boy. He went via the BBC into film production and made such a good fist of it that he’s now a Distinguished Old Maidstonian. I never realised how well he’d done till, at a college reunion in 2004, a gushing actress reacted to my mentioning him as though I were Spielberg’s best mate. Entirely different was drummer Nick Martin, an occasionally spiky youth with a mane of violently auburn hair. His forte was art. He’d end up getting a first in Fine Art at Goldsmith’s, and at the time of his obscenely early death was exhibiting a whole bunch of paintings in the Saatchi online gallery. Though not a loud enough self-publicist to achieve Emin-type fame, he was the most extraordinarily painstaking technician, and evinced in his work a gently warped sense of humour that I always liked. He broke my heart when, after lending me one of his surrealist paintings to adorn my first college bedroom – which knocked everyone else’s Athena posters into a cocked hat – he demanded it back so that he could burn it.

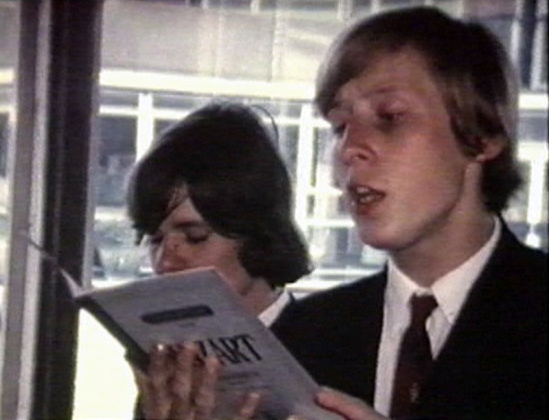

Another future Head Boy sings his heart out in the hope of being spotted by a rock band.

Another future Head Boy sings his heart out in the hope of being spotted by a rock band.

The most talented of us in my opinion was band-leader Martin Woods, whose Achilles heel was a penchant for challenging musical convention that was simply too left-field for most ears, long before Brian Eno. Nevertheless, the imagination he applied to composition was unusually fertile; I still enjoy it. Not that it was a joy to play. He would write super-fast bass-guitar riffs in weird time-signatures that made me grit my teeth with pain and left me with semi-permanently calloused finger-tips, whilst in one composition he included an unaccompanied bass-guitar solo so long and full of technical challenges as to stretch me to the limit, especially in live performance. With growing maturity and improving technology, he developed into not only a consummate guitarist but also a skilled tune-smith and inventive creator of musical atmospheres, in numerous musical genres too. His friend Glyn Jones was the last to join the band, as lead singer and rhythm guitarist. He’d no artistic pretensions, but made his life a work of art, of sorts. Unfortunately, it was a tragicomedy. The life and soul of every party, he was always getting into scrapes even as a schoolboy; and, in later life, he would consume enthusiastically everything that’s best taken in moderation, if at all. After repeated turns for the even worse, it was no great surprise when years of hard living caught up with him for good. Knowing him, he’d have shrugged it off with a smile and a rueful, “That’s rock ‘n’ roll!”

Loader, Jones and Woods look pensive, while Martin gets up to something suitably arty.

Loader, Jones and Woods look pensive, while Martin gets up to something suitably arty.

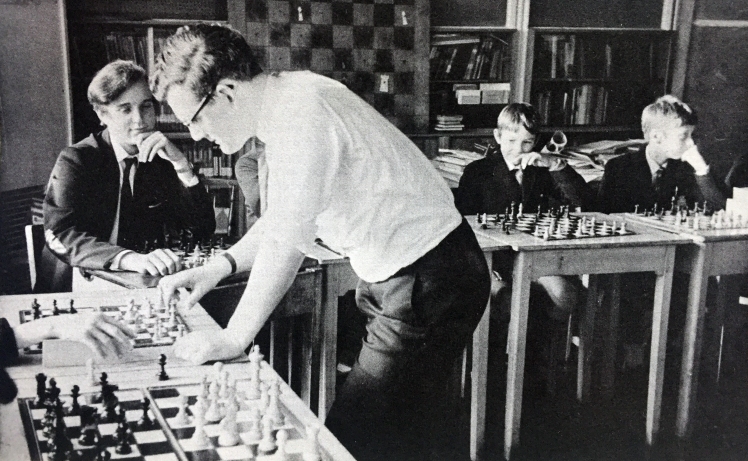

There was a second area in which I grew more productive outside of school hours in the Lower Sixth. I became Secretary of the Chess Club, albeit under less than happy circumstances. The journey from chance entrant in a junior competition to Club official within three and half years is a story in itself, which I’ll try to keep reasonably short. I didn’t actually join the Club until my third year, when I was immediately thrown into a Kent Schools Cup match for MGS Juniors against our counterparts at the Girls’ Grammar. We won 5-0. You couldn’t question the girls’ pluck, because they immediately asked for a friendly rematch with bigger teams; this time, we won 8-0. I played regularly for the Juniors thereafter, mostly on board one, though also a couple of times on a low board in the Senior team consisting largely of 6th-Formers. My highlight was reaching the final of MGS’s Junior trophy, the Martin Wood Cup, though I enhanced my reputation as a bottler at chess by losing to a precocious 1st-Former in a game memorable for me standing up and knocking the whole board and pieces onto the floor; fortunately, we chess players have a good memory for positions. The following year, after losing my first game of the season for the Juniors, I somehow won all the other fourteen I played. This gave me an outlandish playing average, earning me an unprecedented mention in ‘The Maidstonian’ magazine.

My 15 minutes of fame: a fleeting mention in ‘The Maidstonian’.

My 15 minutes of fame: a fleeting mention in ‘The Maidstonian’.

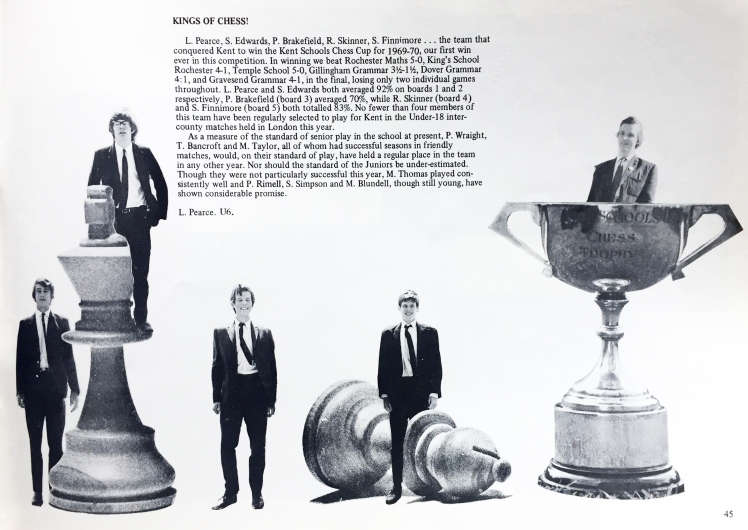

Competitive chess brought me into contact with boys of my own age and similar chess aptitude from other schools, mostly grammar schools, all over Kent. As often as not, we’d have to travel to our competitors, which always made for interesting comparisons. For one thing, I was glad to have missed out on going to Borden Grammar, if only because we regularly thrashed them. For another, it was an eye-opener to play one expensive public school (I forget which) whose team turned up in straw boaters; we thrashed them too. I also loved the ethos of being in a team: enjoying the team spirit on the way to the match, never wanting to let my team-mates down on the day, geeing them up if they themselves fell short, celebrating together if we pulled it off. It was a camaraderie that I would dearly love to have enjoyed on the sports field, had my health permitted. Although I’d had relatively little time for playing chess in the 5th Form with O-Levels coming up, it was a uniquely exciting time for the Club. We had a powerful first team that year, so good that I’d watch them play in competition matches even though not picked myself. Their nicknames are seared in my memory: ‘Fred’, ‘Ed’, ‘Brick’, ‘Lad’ and ‘Flunk’. They smashed their way to a first-ever triumph in the Kent Schools Cup, seldom dropping a point. Though it was exciting to have such a strong MGS team, the consequence was that it wasn’t until I joined the Lower Sixth, and the team was beginning to break up because of A-Level commitments and departures for university, that I got the chance to test my own mettle regularly against the best.

Fred Pearce (top left) trumpets the School’s success in the Kent Schools Cup.

Fred Pearce (top left) trumpets the School’s success in the Kent Schools Cup.

By the 1970 summer term, it was obvious that, with Pearce now entering the 3rd-year Sixth – where he would be taking his Cambridge entrance exams and then leaving at Christmas – I would necessarily be succeeding him as Secretary because the only alternative, Skinner, was required to be Captain. The two of us were duly elected nem con. On the final day of term, however, Pearce informed me that his last act as Secretary was a unilateral decision to split my role into two – ‘Club Secretary’ (me) and ‘Match Secretary’ (another) – ostensibly because, unlike himself, I’d struggle to arrange matches on top of running the club. Pearce, unmistakable with his straight red hair, pale skin and prominent glasses, had always seemed doubtful of my ability, questioning my performances even when the genial Edwards said I’d done well. I’d put it down to resentment at my finishing third in the school Swiss tournament ahead of him and five of his fellow seniors while still only a 5th-Former. I even wondered if he resented my being a U5A boy, whereas all the senior players were solidly ex-U5S and studying Maths A-Level. I now suspect that, being the straight-laced type, he just didn’t approve of my emphasis on playing chess for a laugh. Nearly three years older than me, he must have thought me unbelievably immature, and couldn’t help showing it. He’d already succeeded royally in upsetting me with his annual report in the ‘Maidstonian’, when he’d mentioned several juniors by name but not the regular Board One, me. This, however, seemed to me to be in another league of spitefulness, especially because he appointed as Match Secretary a somewhat modest player I didn’t see eye to eye with. It bothered me all summer.

The Chess Club’s awe-inspiring noticeboard in Piccadilly Circus (left), and a sample exhibit.

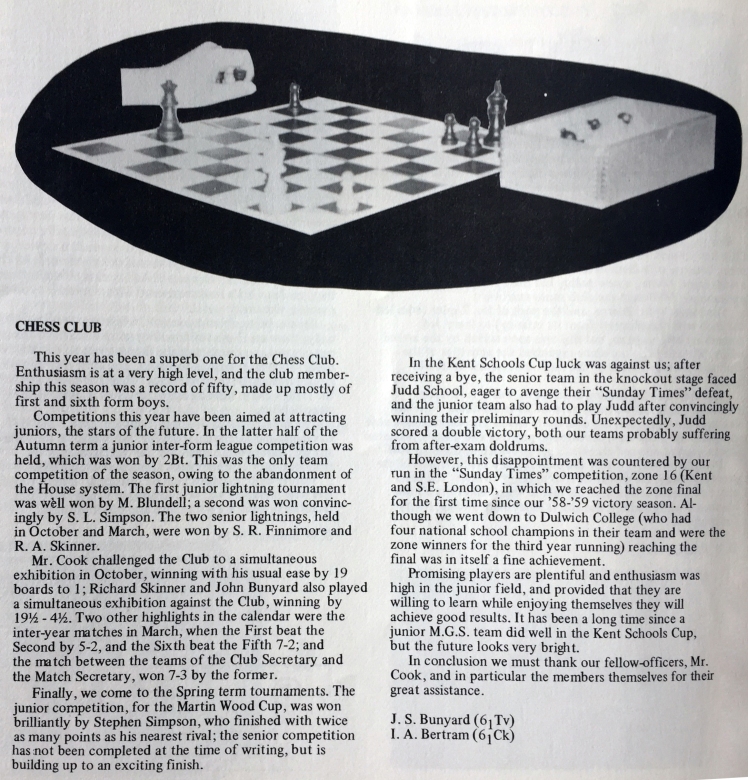

This was however the time when I discovered an important truth about myself: I like a challenge. Perhaps because of the pressures of competitive matches, recruitment had been neglected for years, and there was little talent coming through after Skinner and me. From Day One, I concentrated hard on recruiting youngsters, arranging plenty of tournaments of different kinds and other entertainments. Using marketing skills I didn’t know I had, but which would subsequently make me a career, I ensured that the Chess Club’s notice board was always the most information-rich, the most colourful, and the busiest in Piccadilly Circus. I made a point of befriending as many chess-playing turds as I could; Mr Newcombe would have been proud of me. It must have worked, because the Chess Club paradoxically got a reputation for the din we made. I was able to commence my end-of-year ‘Maidstonian’ report ten months later, “This year has been a superb one for the Chess Club” and truly mean it. Most gratifyingly, when I retired from the role, my successor wrote in the ‘The Maidstonian’ that “Chess thrives in the school as never before” and paid a “very sincere tribute” to the way the club had been run over the last two years. At the time, I thought, “Shove that in your pipe and smoke it, Fred”. With the experience of years, however, I’d be more inclined to congratulate him on an inspired piece of psychology.

My first-ever attempt at journalism, in the ‘Maidstonian’.

My first-ever attempt at journalism, in the ‘Maidstonian’.

It’s only a pity that my match record in the 6th Form was slightly curate’s egg. The trouble was that I became a liability on the big occasion. While I was in the Lower Sixth, we reached the zonal final of the prestigious Sunday Times competition for the first time in a decade. It was our rotten luck always to be located in the same zone as the formidable Dulwich College, who were actually the national champions no fewer than three times in the late 1960s. So did I rise to the occasion? No. Despite having a nearly perfect record in friendlies that season, I lost my game in the final, having already blown it in both the quarter-final and semi-final. It was all down to those infernal nerves, for which witness the fact that, having lost one of those matches with a shocking blunder from a winning position, I soon encountered the same player again in a friendly and beat him with ease. Though these calamities blotted my copybook, I ended up nevertheless with an MGS career average of 79.1% from 43 games, compared with Edwards’s 70.3% from 37, Skinner’s 70.1% from 39, and Pearce’s 64.4% from 45. Even the legendary JS Harris, Captain when I’d been a turd, had averaged only 70.9% from 55. To be fair, they may have played more tough competitive matches than I did; but, as they say in most sports, you can only play what’s put in front of you. I knew all these numbers because my own last act as a Club official had been to condense countless scraps of paper Pearce had left me into a comprehensive compendium of the School’s historical match results. Stupidly, I bequeathed it to my successor. I’ve often wondered what happened to it.

Mr Cook playing a simultaneous against the Club. Behind him is the demo board he used for coaching.

Mr Cook playing a simultaneous against the Club. Behind him is the demo board he used for coaching.

Taking over from the likeable Skinner as Club Captain did provide a great boost to my self-confidence. Being considered best in school at anything at all was evidently quite an achievement for someone who’d started off regarding himself as the educational equivalent of a horse with three legs. It made me doubly determined to live up to the obligations imposed by rank, which in turn obliged me to grow up a bit. After beating Skinner to the Senior tournament title with a 100% record, I played 25 club members simultaneously, winning by 20-5. Most memorably, the Maths master in charge of the Club, Mr Cook, played his usual simultaneous exhibition against us. A county player, the reigning Folkestone Congress champion, and one of the top fifty in the country, he routed us 18-1; but I salvaged some honour for the Club in registering our only point. In fact, I beat him with the very Sicilian Dragon counter-attack he’d taught us at one of his unforgettable coaching sessions in the same room, so he’d in effect been hoist by his own petard. With pleasing symmetry, my final school match was a case of ending where I’d started, against the young women of MGGS. In view of our previous history of embarrassingly one-sided encounters – and perhaps influenced by the fact that, as I recorded in my diary, my opposing captain Miss Cameron was a “nice girl” – I thought I’d act the gallant and, to the consternation of my team, offered each in their team a head-start of one whole knight. This chivalrous move backfired diplomatically when we again whitewashed them.

The marvellous new sports-hall where I made my sporting debut for the School.

The marvellous new sports-hall where I made my sporting debut for the School.

The chessboard wasn’t the only arena in which I’d compete for MGS against a female opponent. Things had changed markedly on the asthma front owing to the recent introduction of bronchodilators. With my breathing difficulties becoming controllable for the first time, I was able to contemplate sporting activities that had previously been out of the question. While I was in the 4th Form – the year when Ventolin appeared – Games master RJ ‘Ron’ McCormick had taken me aside for a quiet pep talk, sharing the story of a friend who’d turned into a good athlete despite suffering from asthma. Without pushing me, he planted the idea that maybe I was ready to have a bash at the mass cross-country run through Mote Park. I decided I owed it to him to give it a go. Despite being horribly unfit, I finished 81st of 128 in my year: not up to my Uncle Tommy’s standard as a Maidstone Harrier, but way better than expected. It gave me a new outlook on what I was capable of having a go at. At length, in the Lower Sixth, I was finally handed the opportunity to do my bit for the School in a sport. Fellow linguist John Thornewell, who’d been teaching me to play golf after school, was also a talented badminton player and was looking to build the school’s contingent of players. I tried it, and enjoyed it. Within a week of teaching me the rules, he selected me to play for the School against – guess who – MGGS. I’m afraid that I lost, but my opponent was immensely sympathetic, telling me that I’d played awfully well in the circumstances. Liar or not, she had charm, that girl.

A typical MGS cross-country run: start together, finish miles apart.

A typical MGS cross-country run: start together, finish miles apart.

That match was only possible by dint of the School’s brand new sports-hall, built on the old games-court behind the canteen. Its particular appeal for me was the facility for five-a-side football, which I immediately thought about the most exciting game ever invented. It didn’t hurt that the matches were short and there wasn’t so far to run up and down. Unfortunately, I remember it best for the time when, after racing at full pelt past my supposed friend Boz Butcher, he tripped me; I still recall being suspended in mid-air like Superman before crashing prostrate onto the highly unforgiving surface. But I got my revenge the next summer. Many of us had become keen cricket fans, inspired not least by Basil D’Oliveira’s test-match heroics that we’d follow during lessons via someone’s concealed transistor radio. After hours during Cricket Week, we’d sneak into the nearby Mote cricket ground through a hole in the fence known to every MGS cricket fan but not, apparently, Kent County Cricket Club. School games consequently acquired a new zest. Now Butcher, a beefy sort, was a dangerous batsman. During a form cricket-match, he hooked the ball venomously towards the deep square-leg boundary. As bad luck would have it, I happened to be fielding there, supposedly out of harm’s way. I saw this solid red missile speeding towards me and had to decide instantly: broken fingers for a month, or coward for life? Stupidly I stood my ground and waited for the agony. The next instant I perceived the ball nestling tidily in my palms and the cheers of my team-mates. I’ll never forget Butcher’s words as he trudged past me on his way back to the pavilion. “Shit”, he said. “When I saw it was you, I thought I’d got a six”.

Edmund Burke: the philosopher who confronted me with my own cluelessness.

Edmund Burke: the philosopher who confronted me with my own cluelessness.

Having no state exams, the Lower Sixth was the least stressful I’d had since my third year. The worst it got was a two-day multi-school seminar that Peter Tree and I were invited to attend, as MGS’s ostensibly most promising linguists, at the now defunct Eversley College in Folkestone. I felt desperately out of my depth the whole time I was there, especially because most of the other delegates were from the Upper Sixth and seemed far more advanced in every respect. I recall only a baffling lecture on Edmund Burke that left me thinking that, if university was going to be like this, maybe I should be looking for a job. That aside, this unusual year was in most senses enjoyable. Because we had only three subjects to study, there weren’t enough lessons to fill up the timetable; so the gaps were occupied by either Private Study periods, when we could turn homework into schoolwork, or else General Studies (GS), a diverse bunch of courses from which we could pick the most interesting. It was under the guise of GS that I started learning Italian in the Upper Sixth. Most memorable, however, was the mind-boggling Astronomy course, where I first heard of the Big Bang hypothesis and its main rival, Fred Hoyle’s Steady State. I remember being most indignant about the latter on the basis of mere plausibility, and was delighted when it was thoroughly debunked years later. The experience started me on a lifelong interest in cosmology, relativity, quantum, and particle physics. It also made me realise that I’d been corralled into entirely the wrong subjects.

Scenes from Paul Ryan’s movie, with Young Bunyard serving as rugby linesman (far right).

Scenes from Paul Ryan’s movie, with Young Bunyard serving as rugby linesman (far right).

The highlight of Activities Week in the Lower Sixth was a Super 8 film-production project led by Paul Ryan, who’d been with me in the G-stream but now gone over to the Sciences. With the benefit of his nifty camera work, a comedy movie came together, consisting of a series of Pythonesque skits loosely based on School life. Some turned out surprisingly funny. I featured in one myself, dithering for an eternity over a chess move before the camera panned across to my opponent: a skeleton, borrowed from the biology lab, dressed up in school clothing. Sadly, that movie is now lost. Ryan was by this time already something of a veteran, however, having completed a 45-minute documentary of the School as it was in 1970-1. Presented by the Head Boy, Martin Passmore, it was a professional piece of work, especially considering the limited technology of the day. My only beef was with the title, “One Day We Shall Remember”. This was the usual mistranslation of the MGS motto, “Olim Meminisse Juvabit”, which actually means something like “One Day One Shall Take Pleasure In Remembering”. But this itself was a cheat. As all we Latinists knew who’d studied Virgil under Killer, the original quote – spoken by Aeneas to his downhearted crew when they’d just been shipwrecked – was “Forsan et haec olim meminisse juvabit”. The key word here is “forsan”, meaning “perhaps”. The sense of it was, “One day we’ll enjoy remembering even this – maybe”, which actually captures most Old Maidstonians’ sentiments rather more precisely. Never mind. Ryan’s experience did him no harm: he went on to a highly successful career in TV production.

Lost in translation: the MGS motto, a more sanguine watering-down of Virgil’s original.

Lost in translation: the MGS motto, a more sanguine watering-down of Virgil’s original.

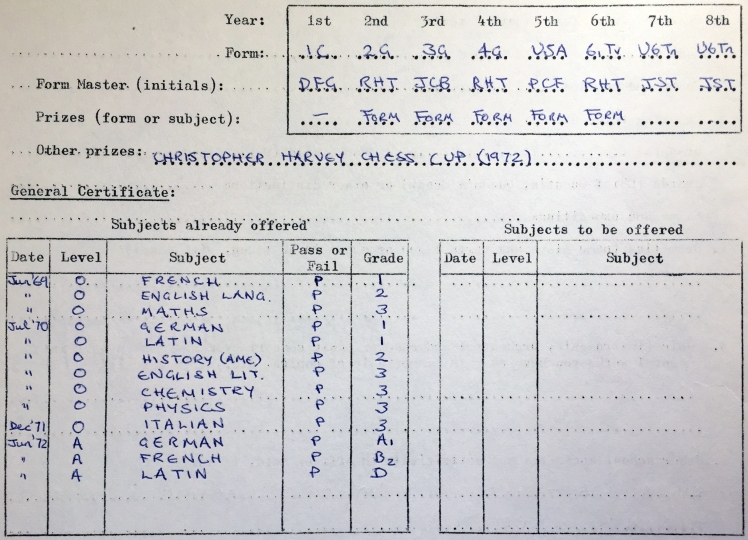

If the Lower Sixth was the lull, the Upper Sixth provided the inevitable storm. There’d be no more safe refuge provided by Mr Traves, who strangely went off to work at Maidstone Prison. Instead I found myself back in the main building at Piccadilly Circus in the hands of a new and very different form-master. This was JS ‘Jake’ Tresilian, an unforgiving type who could have had a good career in Hollywood playing the Munsters’ butler. A generation older than the fun teachers I’d had the year before, he was actually intelligent and fair, but not long on tolerance or humour. He personified the school-year to come, which turned out a tale of one formal trial after another. Late in 1971, I took the last of my ten O-Levels, Italian, which we’d had three months to prepare for from scratch. It might sound a tall order, but it wasn’t so bad when you’d learned both Latin and French and got the hang of how Romance languages work. I managed a grade 3, which has proved its worth at countless trattorie ever since. Another slightly oddball test was the ‘Use of English’ exam I had to take in March: the literacy check required for entry to Oxbridge that was downgraded in later years to an English O-Level. Intended no doubt to weed out candidates from overseas who hadn’t mastered the vernacular, I did sense that it was also a cunning way of spotting trouble-makers with opinions deemed unsavoury at the new Oxford. It was a gimme, so long you just minded your p’s and q’s.

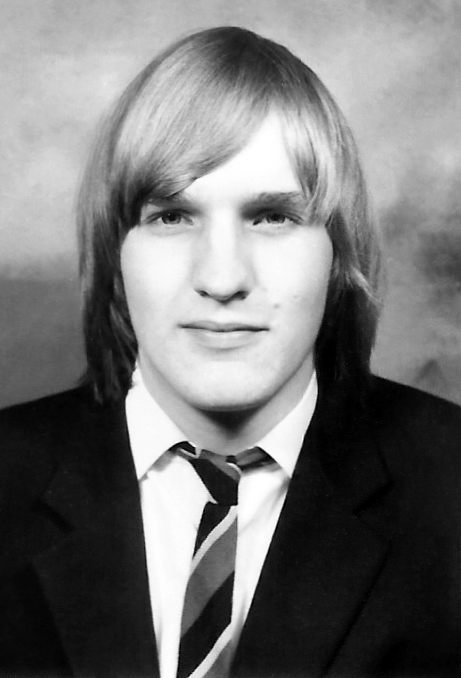

Young Bunyard in the Upper Sixth, now with long hair and fashionably loose prefect’s tie.

Young Bunyard in the Upper Sixth, now with long hair and fashionably loose prefect’s tie.

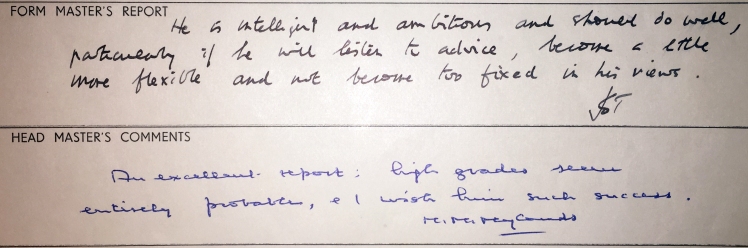

In between those, the early part of 1972 was given over to mock A-Levels, the dress rehearsal for the summer’s big event. Without the pressures of a state exam, I didn’t find them too bad and, after getting decent marks and positions across the board, I concluded that there were reasonable grounds for complacency. My teachers had to find something to say in my report, obviously, so Mr Tresilian decided to put on a dampener by saying that I needed to read more and plan my answers better. German master Mr Gentry went further, writing, “He was rather let down in this examination by timing problems in the literature paper, and will have to adapt his present thorough but lengthy essays to the limitations of a three-hour examination”. Now, this wasn’t a new problem. As early as the 3rd Form, an English exam essay of mine had trailed off with “By the time he turned the corner, they had gone.” – which examiner Mr Ridsdill-Smith had pithily continued with “…and so has your time” before lambasting my poor planning and marking me down. My own belief was that the exam system needed to adapt itself to pupils who knew enough to complete more than three hours of content instead of struggling to find enough to say. Mr Tresilian had the last word, however, commenting that “(he) should do well, particularly if he will listen to advice, become a little more flexible and not become too fixed in his views”. Ouch.

Mr Tresilian’s caustic advice, and acting Headmaster Mr Rylands’ undue confidence.

Mr Tresilian’s caustic advice, and acting Headmaster Mr Rylands’ undue confidence.

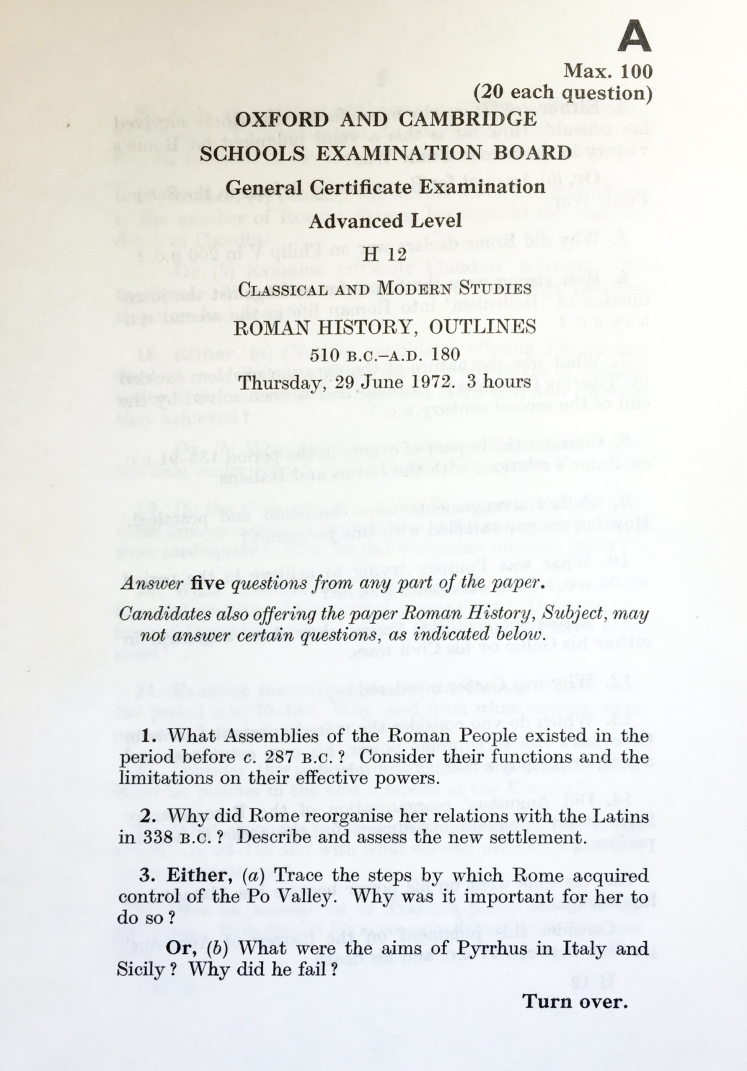

Late in June, it was time for the serious stuff. There commenced three weeks of almost continual A-Level exams, in addition to which I took the optional Special papers in French and German that were meant to provide additional guidance for universities. None of it was easy, but the German proved as near to a pleasure as I could hope for. The French didn’t seem all that tough either, though it did leave me wishing that I’d done more vocabulary revision and re-read the texts instead of just my essays. My only concern was that I’d failed to finish some papers; but maybe other candidates had, too. Latin, on the other hand, was a calamity. I’d no idea how well I got on in the language paper: it was no more or less tough than usual. What I can say with certainty about both the literature and history papers is that I liked the questions, but made a classic hash of timing. Ironically, Latin was the one subject where I’d had no timing problems in the mocks; yet, in literature, I completed only six of the eight questions. History was even worse: I finished just three of the five, plus a meagre paragraph on Sejanus, whose story I knew so well that I’d told it to friends; here it would earn me next to nothing. Leaving the hall, I felt sick. I worked out that, even if I scored a very creditable 75% on each of the three questions I’d completed, I’d still struggle to get 50% overall. This had to put pressure on my ability to get even a B-grade. What would Oxford think if I got two As and a C? It was hard to imagine that they’d go for it.

The fateful Roman History paper that provoked the decline & fall of my exam technique.

The fateful Roman History paper that provoked the decline & fall of my exam technique.

My summer holiday in 1972 would be the last I’d get for a while, my parents having increasingly left me to look after myself without giving me the financial wherewithal to do so. Fortunately the School had ridden to the rescue. They’d come looking for boys willing to do an exchange visit. My parents agreed, and in July we said hello to Georg Stamm, who turned up on the day of my last A-Level paper, and had to come to school with me for the last ten days of term. Eventually I took him to London, where we spent seven hours continuously walking from sight to sight, avoiding areas left derelict by the Luftwaffe. Despite this success, Georg took his retaliation for all the boring days when his parents collected the both of us in their VW on their way back home to Dillenburg in Hesse, north of Frankfurt am Main. We did little but play putting and boules, and at times got so fed up with each other’s company that we’d start hitting or hurling the balls at each other. The saving grace was his parents, particularly the father Karl-Heinz who, as a teacher, was keen to take the opportunity to induct me into subversive German literature. In his study, we together read Büchner’s fragmentary ‘Woyzeck’, an enthralling piece which taught that immorality was the ineluctable consequence of poverty. Though seriously meant, it was an idea that would have prompted ribald laughter back on the Shepway estate.

Exploring Dillenburg and Limburg with the three Stamms.

Exploring Dillenburg and Limburg with the three Stamms.

It was while I was away that my A-Level results were published. Naturally I was nervous about how I’d done, having no inkling of what lay in wait. When I finally got to see them, one letter immediately caught my eye and made my heart lurch into my mouth: a capital D after Latin. Next to it was another letter almost as surprising: a B for French, with a 2 in the special paper. The A1 in German was a relief in the circumstances, but not much of one. Plainly I had no chance of getting into Oxford. Perhaps this was a blessing in disguise, I post-rationalised, because I was better suited to London University anyway. I phoned Mr Tresilian to confirm that I needn’t bother to show up in the autumn for the Oxford entrance exams. Nonsense, he said; my grades were fine. I suspect that he was actually thinking, “That’ll teach you, you cocky sod”. As for me, I couldn’t quite believe what he was saying. I told him straight: “B A D spells BAD”. He laughed suitably lugubriously, told me I was over-reacting, and informed me that he would be expecting me back in his class next month for the extra term that would constitute my ‘Third Year Sixth’. I had to tell the London colleges that, if I was going to accept one of their offers, it wouldn’t be for another year yet.

Hardly Oxbridge material: the underwhelming finish to my school exam history.

Hardly Oxbridge material: the underwhelming finish to my school exam history.

The new challenges of the Third Year Sixth started even before I returned to school. My mother chose this of all moments to move from a bungalow conveniently situated a dependable 10-minute bike-ride from MGS to another bungalow out in the sticks, a half-hour coach-ride away on the infrequent Maidstone & District service. It was less than ideal for someone who already had a punctuality problem, and now had some crucial tests coming up. The Oxford entry exams were spread over three days at the end of November. Fairly typically, I vomited on the way to school on the second day. Otherwise, I don’t think that I found the tests quite as daunting as the A-Levels: the general paper gave me the chance to rant about modern poetry of the kind I’d been exposed to on an all too regular basis in ‘Original Contributions’, and the French and German translations were not impossible; it was only a lack of vocabulary – even English – from too little reading over the years that caught me out. I couldn’t help feeling that I was just going through the motions, anyway, which helped ease the pressure and take away the nerves.

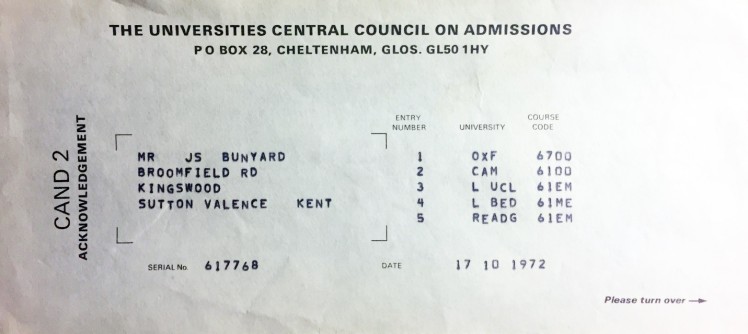

My five choices for further education: Oxford, Cambridge, UCL, Bedford College London, Reading.

My five choices for further education: Oxford, Cambridge, UCL, Bedford College London, Reading.

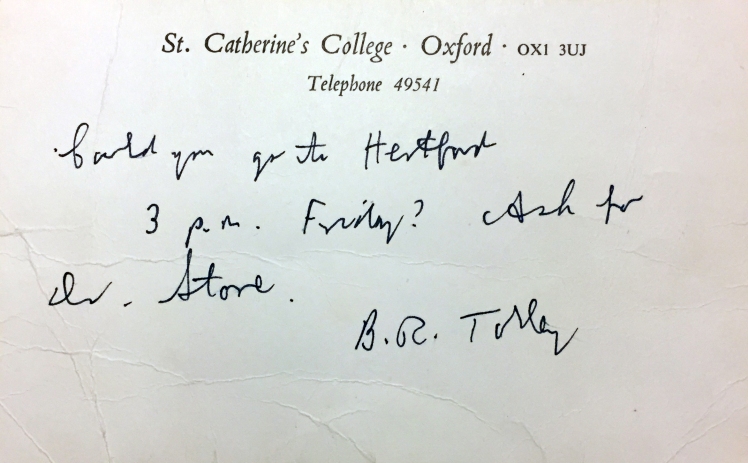

By then, I’d already been up to London with Mendes for interviews at Bedford College, which I’d loved; but the main event came in mid-December when Tree, Thornewell and I went to Oxford for two days of interviews. At St Catherine’s College, known as ‘Catz’, I met the French tutor Dr BR ‘Bruce’ Tolley, who unfortunately reminded me of nobody so much as Bernie Moody. Luckily, he was more than balanced out by German tutor TJ ‘Jim’ Reed at St John’s College, a wonderfully laconic and ironic character who paid me an amusing backhanded compliment in remarking how ably I’d plagiarised one of his works in the entrance exam. I additionally had a just-in-case interview at Hertford College, memorable for my arriving early for once and, while waiting on the staircase outside the professor’s door, hearing him say to his colleague on the way up, “If we can get this Bunyard, we’re laughing”. When he saw me already there, he had a face the colour of a beef tomato, and blamed me for being punctual. That was the moment when I realised that I wasn’t just wasting my time.

The only time Young Bunyard surprised anyone by being on time.

The only time Young Bunyard surprised anyone by being on time.

I have to admit that I didn’t even want to go to Oxford. I was pushed into it. Mr Traves had started applying the pressure a year earlier, insisting that I’d be ideal for his alma mater, Queen’s College. I much preferred London, both because it would be far easier to get to, and because its co-educational policy looked more appetising than Catz’s male homogeneity and Oxford’s 4:1 preponderance in favour of men. Not only that, but the courses at University College (German and Danish) and Bedford College (German and Dutch) would spare me having to do any more French literature, some of which I was beginning to dislike with a passion. Naturally, no one around me supported this ambition. Most persistent was our kindly new headmaster Dr PAJ Pettit, known on account of his qualifications (M.A., D. Phil) as Mad Phil: a decidedly liberal sort after the abominable Bernie. He invited me to his house one evening – the first time I’d ever been in there – and insisted that I’d be an idiot to turn down the chance to go to Oxford, an honour for which most pupils would give their eye-teeth. He came up with all manner of other arguments, so that I ultimately felt partly persuaded but mostly browbeaten into agreeing.

The altogether more liberal new Headmaster, ‘Mad Phil’ Pettit.

The altogether more liberal new Headmaster, ‘Mad Phil’ Pettit.

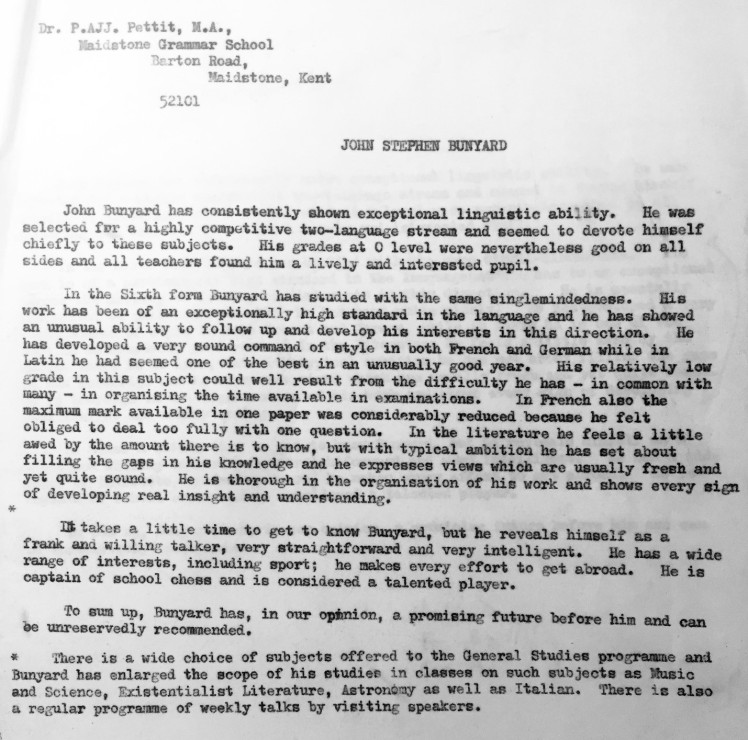

What I didn’t know was that, back in October, the acting headmaster RR Rylands, whom I’d never particularly got on with, had written to Dr Tolley in the new Headmaster’s name with an impassioned recommendation that Catz accept me. After arguing that I was a good student whose A-Level exams had been messed up by poor time-management, he wrote a glowing appraisal, concluding that I was “unreservedly recommended”. He said nothing about my impoverished background, my stop-start education, my ill health, the death of my father, my domestic circumstances, or any other excuses that would weigh heavily today. His only argument was that I deserved a chance on merit. Irrespective of whether the School had its own motives, it was a remarkably generous thing to do for a lad who quite honestly had let everyone down, not least himself.

Begging letter: Mr Rylands’ draft of the special plea put in for me by the Headmaster.

Begging letter: Mr Rylands’ draft of the special plea put in for me by the Headmaster.

My last formal event at the school, Speech Day on December 6th, 1972, saw me collect not only a fat Brockhaus German dictionary as my sixth and final form prize, but also the senior chess trophy, the Christopher Harvey Cup – the only time a silver cup ever had my name on it. On December 19th, I left the School for good, and immediately commenced a Christmas postal round in my newly acquired red Mini, having just passed my driving test. It was on the last day of my round that I heard the news: Catz had accepted me. Dr Tolley had written to say that, having turned down two or three Modern Languages candidates from MGS in the past few years, it was “a special pleasure” to take me, which surprised me from a man who’d seemed to take pleasure in nothing much. Apparently I’d impressed at interview and my entrance exam marks had been good, so that my A-Level results were all a bit, um, academic. He also mentioned that he’d been interested to hear about Ian Nicholson and Nigel Norman, whom he’d lost track of. The fact that these two amiable teachers were both Catz alumni had of course been the main reason why I’d put that college at the top of my Oxford preferences. Whether it was a good enough reason is another story, and another blog or two.

Young Bunyard collects the cup from guest speaker SV Peskett, with ‘Bob’ Rylands doing the spadework.

Young Bunyard collects the cup from guest speaker SV Peskett, with ‘Bob’ Rylands doing the spadework.

Strangely, I would be back at MGS within a year to collect another prize on Speech Day. I’d been a bit miffed that Mendes picked up the Kenneth Sawdy prize for German: we were the only two to get grade 1 in the Special paper, and I always felt that the equitable division of spoils was Latin to him and German to me. The next year, however, it really was awarded to me, albeit twelve months after I’d left, because no one that year was deemed up to scratch; Tree picked up two other prizes on the same grounds. We were handed them by Jo Grimond, whose Liberal Party leaderships bookended that of Jeremy Thorpe, the man now remembered only for his Very English Scandal. It would be many years before I went back again, and then only to an Old Maidstonians (OM) dinner that disappointed a little in the number of old friends present. Over the years I was lured to one or two more such events; but it wasn’t until about ten years ago, when Nigel Viner’s two sons were at the School, that we started regularly entering the PTA’s annual quiz in February with our wives and two other couples; we even won it once, satisfyingly beating the teachers’ table into second place. Five years ago, four of us started entering the OMS quiz in October. After being beaten into second place – by a team who’d scored about 70 points less than us in the actual quiz, but made up the difference through a bizarre bonus gimmick – we re-entered the next year as the ‘Sore Losers’, and won the cup twice in a row. A big part of our success was down to Keith Rylands, my fellow Maidstone United fan and younger son of the same Mr Rylands who’d salvaged my Oxbridge entry.

The Sore Losers winning in 2017, with Keith Rylands lurking behind.

The Sore Losers winning in 2017, with Keith Rylands lurking behind.

During one of those events, I met Lois Birrell, who as the School’s archivist at the time was distributing old boys’ school records to their respective subjects, instead of doing what less enlightened archivists do today with unwanted documents, which is to throw them into a skip. Through her, I came to have a one-to-one with headmaster Mark Tomkins. Two things struck me about him. First, he was remarkably tall. Even as a six-footer I got a stiff neck looking him in the eye, and was glad when we sat down. Second, he was remarkably energetic, both physically and mentally. Since he is still the incumbent, I’ll not embarrass him; suffice it to say that it’s a pity he wasn’t on the scene half a century earlier when Bob Rylands was looking for a successor to Mr Claydon. I gave him a preview of a 75-minute movie I’d made, called ‘The Neuro Files’: a sort of musical journey through the brain. It had come about when my old Rookie band-mate Martin Woods contacted me out of the blue after nearly 30 years, asking if I’d like to collaborate on a musical project of my choosing. Since I’d been thinking for a long while that people would benefit from knowing how their own brains work, and that the arts were a most amenable way of communicating complex ideas, I was up for it. We pulled in other collaborators and named ourselves SiM, for ‘Science in Music’. A 20-track CD emerged, to which I then applied the film-making skills I’d acquired over the years (sparked no doubt by my 6th-Form experience at MGS) to make the movie. A health-and-wellbeing enterprise now wanted me to turn it into a teaching resource, and I wanted Mr Tomkins’ opinion.

The ‘Neuro Files’ DVD, bringing the sounds of Rookie back to MGS after 40 years.

The ‘Neuro Files’ DVD, bringing the sounds of Rookie back to MGS after 40 years.

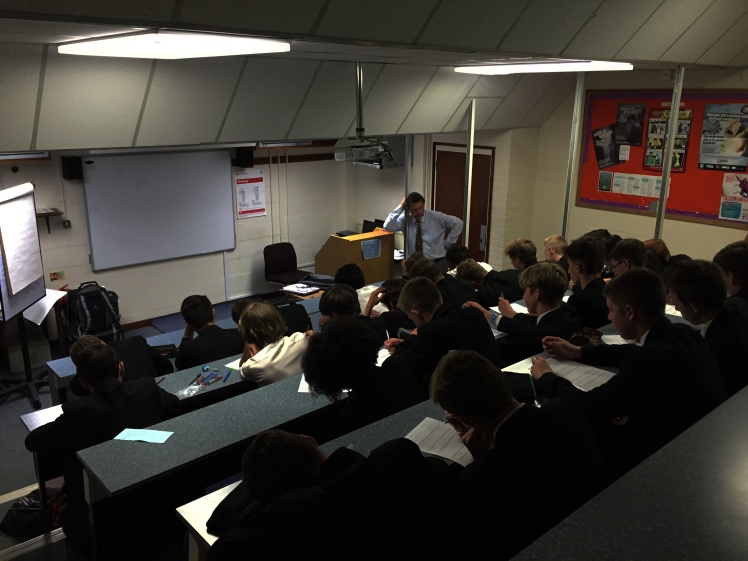

Mr Tomkins’ opinion turned out sufficiently positive that I got a unique chance to renew my acquaintance with the School. He suggested that I preview the film to a class of Year 10 (4th Form) boys, and also teach some of the lesson plans I’d drafted. It duly happened, under supervision, in June 2015. True, the project didn’t get off to the best start. It was made plain to me that the project was not universally welcome among the staff; but I’d got used to the Semmelweis Effect by then (look it up), and knew that the only way to deal with Luddism is to press on regardless. I’m glad I did, because the project was ultimately a joy. I say “ultimately” because it did take a while to slip into the culture. The thing that most struck me was the well-documented sea-change in societal conceptions of discipline today. It wasn’t that everyone was less well behaved, but rather that a small portion of each class – usually a table of four – seemed to consider itself outside of the School’s jurisdiction, and treated the goings-on around them with something like disdain. I saw only one instance of a (more experienced) teacher truly getting to grips with such rebels; they were otherwise left to get on with their private conversation. I only persisted with my first lesson because one boy in particular looked riveted throughout. But the film screening was worse. At first one small group began misbehaving, then another. At length, so many of the audience were talking aloud among themselves that one of the two joint deputy-heads in attendance decided to halt the exercise. The other took a different view, however, told them to shape up, and restarted.

The test audience delivers its verdict on the ‘Neuro Files’ movie.

The test audience delivers its verdict on the ‘Neuro Files’ movie.

I was half inclined to give it up as a bad job, especially when they handed in the opinions they’d expressed in questionnaires and it was evident at a glance that as many had disliked the experience as liked it. Yet, bizarrely, the Q&A session that followed proved about the most enthusiastic I’ve ever witnessed. Their big problem, the critics said, was that just watching the movie gave them no opportunity to ask questions – which struck me as a perfectly good reason to be irritated. Now they’d started throwing questions at me, I couldn’t stop them. When I eventually hurried away to my next lesson, I was pursued by three or four boys asking yet more. One followed me as far as the threshold of the classroom, where he asked “Sir, what else does the Anterior Cingulate Cortex do?” This stopped me dead in my tracks. I turned, looked him in the eye, and asked him, “How did you remember that?” With a grin he rolled up his sleeve and showed me: he’d copied it in ink, letter-perfect, from elbow to wrist. It’s moments like that which must make teaching a joy, whatever else there is to put up with. I got an even better surprise when we analysed the questionnaires completed by the pupils (or “students”, as they’re now known for some reason I cannot fathom) after the classes. A handful had hated it, and could find nothing good to say. The rest either liked it, or loved it; six in ten wanted to learn more about the brain on the strength of just one lesson, whilst nearly two in three said it would encourage them to take a STEM subject (Science, Technology, Engineering, Maths) at A-Level. It was astonishing. This polarisation took me back to Mr Blackman’s efforts to deal with mixed-ability classes at Molehill Copse, when he’d separated three columns of kids who just wanted to learn from a fourth column who only wanted to be out on the streets. You had to admire the ones whose thirst for knowledge remained undiminished by the distractions.

The 1981 extension, with the Performing Arts Centre to the right and the 1960s block to the left.

The 1981 extension, with the Performing Arts Centre to the right and the 1960s block to the left.

The results of those trials impressed the committee of the PSHE (Personal, Social, Health and Economic) Association committee, and that breakthrough led to two more socially beneficial projects that are now in the field; so the School’s contribution turned out a significant one. I didn’t see Mr Tomkins again for a couple of years or more, when he invited me back to take a look at building works that had been going on in the meantime. I accepted because I was interested to see more of the 1981 extension to the southern wing that I’d hurried through on my way to the excellent lecture theatre where I’d shown the movie. I admit that I accepted with a little trepidation: new works must surely mean more of the same horrors that had been tacked onto the original quad. I was to get two surprises. The first was being given a very extensive tour by none other than the Head himself. The second was discovering that the additions were not only extensive, but also tremendous. The modernist Small Hall block had been demolished, as had the barracks, the log cabin, the caravans, the scout hut, the fives court, and even the freezing swimming pool. In their place stood four substantial new edifices built for the modern age: a Science & Computing block, a Food Technology block incorporating a 6th-Form lounge, an Applied Learning Centre, and a Performing Arts block, with tennis courts where the pool used to be. Not only were these new buildings packed with facilities we couldn’t even have dreamt of; they also cohered better architecturally with both the original quad and the 1981 extension. Even if the 1960 southern add-on still stood out from the rest, the overall improvement was obvious.

Some of the mind-boggling facilities available to today’s ‘students’ – the lucky devils.

Some of the mind-boggling facilities available to today’s ‘students’ – the lucky devils.

Nor had the process of improvement finished. With the school headcount already up to 1,270, and expected to rise further in line with the region’s steepling population, the shortcomings of the original design for the current age were apparent. The attractive old pavilion, well past its use-by date, was scheduled for demolition. In its place, a new sports centre was being built in the south-western corner of the school field, with plans to add a second storey in due course. What’s more, Mr Tomkins told me of a scheme to expand the library by merging the space with the original art studio next door, which was superseded in 2011 by a spacious affair inside the History, Maths and Art block (there’s eclectic for you) beyond the new canteen. The project would not just involve building works. A school library nowadays is more like a study portal, he explained, where the internet is used to access a world of information; so the need was for IT equipment, not just books. The OM Society was leading the charge to raise the money for the works, and one OM had laudably offered to match whatever they raised pound for pound. It’ll be just fine by me if the project comes to fruition, and the location of the Willie Fawcett incident is finally obliterated; though they might also like to commemorate Stephen Box’s immortal ‘Holy smoke!’ joke with a blue plaque.

The sexy new art studio (left); its predecessor (right) stands ready to be merged into an augmented library.

The sexy new art studio (left); its predecessor (right) stands ready to be merged into an augmented library.

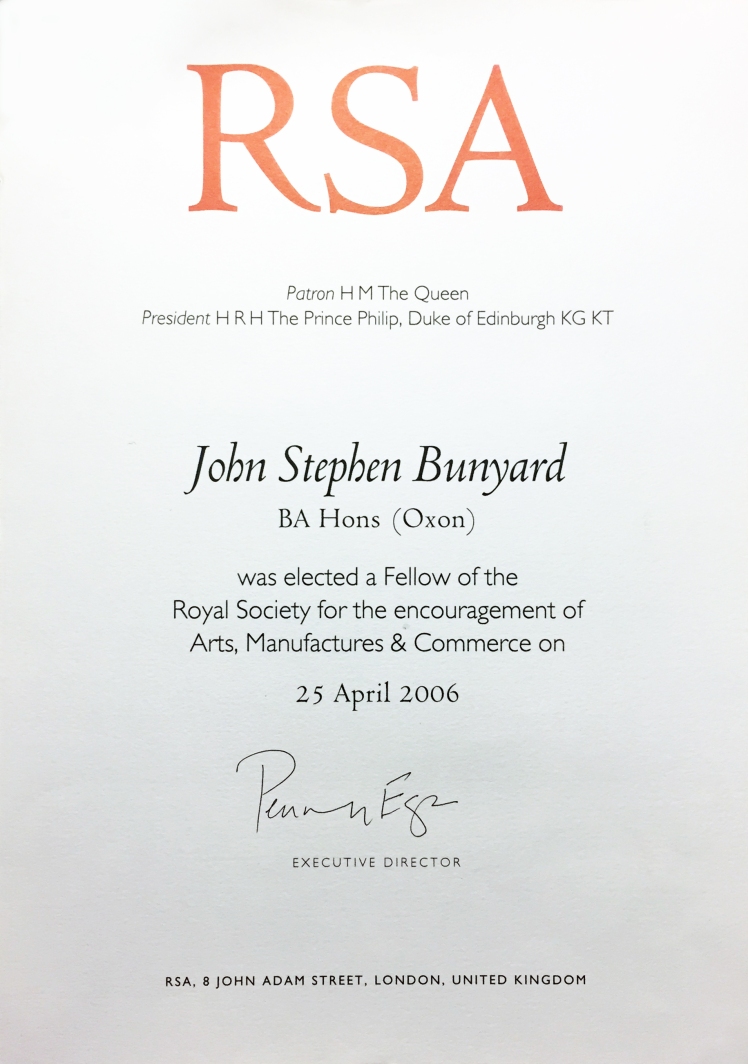

That isn’t quite the end of my MGS story. A decade ago, I was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts, a body created to stimulate commerce, manufacturing, science and the arts for the benefit of society. I was delighted to have the honour because I’d long admired the Society’s intentions, and in particular relished the fact that it was founded exactly 200 years before my birth by William Shipley, a born and died Maidstonian. Sadly, it didn’t turn out the way I’d expected. The new CEO, political adviser Matthew Taylor, had turned the RSA into something resembling a talking-shop for right-on plutocrats. As I saw it, perhaps a little cynically, the deal for members was that one could expect to partake of government largesse in return for propagating the Blairite credo. One of the members’ new shibboleths was that grammar schools were a disgrace and must be eliminated. This I found hard to swallow. Having been born with a plastic spoon in my mouth, I’d always believed – like most of the other kids at Molehill Copse, I suspect – that the Grammar and Technical Schools offered the best way out for those able and prepared to improve themselves. Even all my academe-free relatives swore by them. As Brecht said about something entirely different, “If they didn’t exist, you’d have to invent them”.

The RSA: brainchild of a Maidstone man.

The RSA: brainchild of a Maidstone man.

Of course, I’d been hearing the other side of the story since I was a kid via the news. I hadn’t known when I took the 11-Plus that I’d be going into secondary education at a pivotal time in British educational history. The grammar-school system of England and Wales was high among the ideological pet hates the incoming Labour government was out to address. Their demolition expert was a heavyweight: Anthony Crosland, author of ‘The Future of Socialism’, one of those landmark efforts to reinvent belief systems for new ages. “If it’s the last thing I do, I’m going to destroy every f***ing grammar school in England”, his widow reported him as saying. The main reason for this, I learned later, was that he considered it unfair to differentiate kids on the basis of the 11-Plus when they might come good later. I naturally wondered why it was then logically right to set exams measuring relative ability at any age and in any discipline. More specifically, I wondered why Crosland thought it fairer to mix everyone up than to segregate us according to ability. Hadn’t he heard the stories I used to hear every day from my sister about the mayhem that went on the whole time in secondary moderns like Senacre, which were now being hopefully rebranded ‘comprehensives’? Wasn’t he aware that many kids there resented being kept at school to learn middle-class tosh they neither wanted nor needed, and would much rather be out earning money?

Public schoolboy Crosland’s magnum opus, in worryingly National Socialist livery.

Public schoolboy Crosland’s magnum opus, in worryingly National Socialist livery.

The answer to both questions was of course no, and I soon worked out why. When Crosland appeared on TV, he just didn’t sound like one of us. He was, in fact, a public-school toff. Whereas other Labour ministers came across as working-class Northerners, Crosland looked and sounded like a Tory. He was, in fact, the first champagne socialist I’d come across, albeit the first of a good few. It was hard to imagine that he’d been on the inside of a council house in his life, let alone lived in one. My mother hated him. Strangely enough, from the opposite side of the political spectrum, my father thought him a twerp too. As for me, although the Daily Mirror assured me that I could feel safe in his hands, I instinctively felt distrustful of both his analysis and his motives. This was not so surprising coming from one who not only was one of the winners in the 11-Plus challenge but also from Kent, the heartland of the grammar-school movement. Yet my belief never wavered, despite the leftist direction my politics would take at university – a conviction in which I was by no means alone there. It is perhaps unsurprising that Crosland slipped through his anti-grammar school measure in the undemocratic form of a government directive, Circular 10/65, thereby circumventing the fierce resistance any bill would have met in Parliament, where Labour’s majority was wafer-thin. The issue was not dead, however, and would come back to bite me when I joined the RSA.

The RSA: not the kind of club I’d want to be a member of.

The RSA: not the kind of club I’d want to be a member of.

Crosland’s spiritual successor was Shirley Williams, who not only waged war on grammar schools from her own ivory tower but was happy to do so under two different political flags. At the RSA, I met a second incarnation of her. I was invited to a convocation in Canterbury, the purpose of which was evidently to take New Labour thinking into a Tory stronghold. The very first person I talked to revealed without batting an eyelid that she was from Manchester and had moved to Kent specifically to “eradicate” the horror of grammar schools. I did suggest that, yes, that might be a tidy way of keeping the oiks in their place, but the irony was wasted on her. In her mind, grammar schools were merely Tory redoubts. Smash their schools, and you cut off the Tories at the knees. I didn’t say anything, having learned that arguing with an ideologue only makes her angry. But I did laugh inside, remembering what a fantastic job grammar schools had done in my experience of turning middle-class youngsters into card-carrying leftists, and also how many hard leftists had been radicalised by failing the 11-Plus and concluding that, since they were perhaps not best equipped to compete within the system, redistribution of wealth looked like their best way forward. Considering also what a boon grammar schools are to working-class kids when they’re made available to them, I’ve never understood why the political left doesn’t embrace them as the siege engines of the revolution. But then, as the great polemicist Swift was fond of pointing out, ideology defies reason; and the expediencies of a particular age, or year, or moment readily become doctrine for all time. Encountering that harridan persuaded me to walk straight out of the RSA. I never went back.

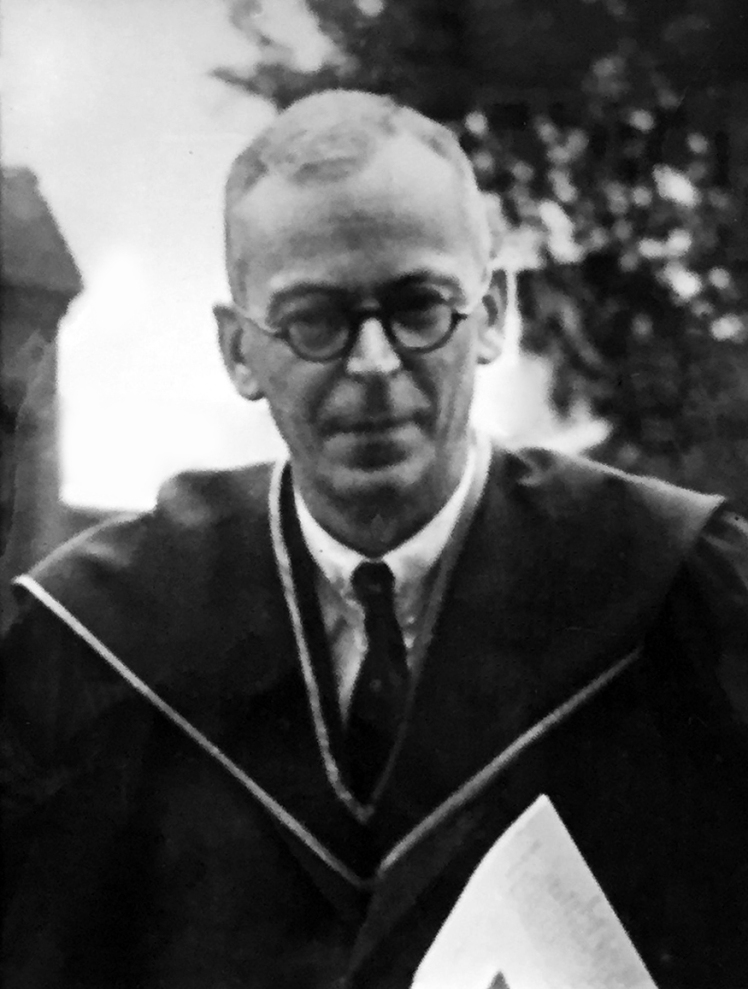

W Arthur Claydon, Headmaster 1941-66: a grammar-school loving leftist.

W Arthur Claydon, Headmaster 1941-66: a grammar-school loving leftist.

It’s ironic to reflect that, at his very last Speech Day and my first, the outgoing headmaster Mr Claydon had used his Report to take issue with Crosland. Ironically also a previous headmaster of the Borden Grammar School I so nearly attended, he was described in the ‘Maidstonian’ on his departure as a realist who nonetheless had a “burning faith” in grammar schools. From his leftist perspective, he regarded the undermining of well-functioning grammar schools as a betrayal of the very kids Crosland purported to be concerned about. The dispute meant nothing to me at the time, but I can well imagine now how the developments of the following half century would have dismayed the old boy. I think he’d have been consoled, however, by the MGS of 2018 that Mr Tomkins allowed me to see close up. For one thing, it would have been a relief to find it still there, and still doing pretty much what it had back in his day. The changes wrought in Mr Moody’s time, having failed, had been undone over time. Admission was again available to 11-year-olds. The house system was back, and with the rather better nomenclature of Barton (formerly School), College, Corpus Christi, and Tonbridge (West Borough). The CCF and sports seemed to be in rude health. The ‘Maidstonian’ was no longer spewing forth the atrocious ‘Original Contributions’, though admittedly this had something to do with the fact that the whole magazine had been axed. Aside from the new facilities and architecture, the only obvious change was the presence of some 6th-form girls. Academic standards were back in fashion, too. During my occasional visits to the Big Hall over the years, I’ve mused about future archaeologists who will one day dig it up and write learned papers about their discovery that, where once only the names of Oxbridge and London scholars and exhibitioners had made it onto the walls, by now an A grade at A-Level would suffice; and they’d construe it as evidence of the nation’s 21st-century slide to barbarism. Here, however, was a Headmaster who welcomed the recent resurrection of academic standards, and was doing something about it… which, funnily enough, is what grammar-school headmasters used to be hired for, once upon a time.

Only the best: the days when you needed a top award, and had preferably performed with Rookie.

Only the best: the days when you needed a top award, and had preferably performed with Rookie.

It’s telling that now, half a century after Crosland, grammar schools are more in demand than any other kind. The Bolshevik-turned-counterrevolutionary Peter Hitchens (brother of Christopher) opined recently that, wherever their abolition in large parts of the country wasn’t down to ideological bone-headedness, it was the work of the faction who during the Cold War sought to debilitate Britain by undermining its institutions, and neglected to stop doing so even after the Russians stopped paying them. It sounded a bit paranoid, until I read of a top American university that’s now actively discouraging dependence on empirical evidence in favour of ‘personal stories’. If he’s right, Crosland’s drive to deprive the public of its best state-schools would have to be construed as a crime against society. I’ve no ideological flag to wave for grammar schools; but, as a pragmatist, I share Mr Claydon’s view that you don’t fix something if it ain’t broke. I know that some of my best school-friends will disagree on the strength of their personal experiences, and I do sympathise; but I have to speak as I find. Unless you subscribe to the 19th-century theory that you can only build a model society by first destroying the existing one – a procedure that history has shown to be singularly bloody even for the perpetrators, and mostly counter-productive – you have to believe that life is about making the best of what’s out there in the real world. I’ve never been the type to take particular pride in institutions, yet listening to the enthusiasm of some of the kids at the School gave me a warm glow; as did the vision expressed on the School’s website. Fortunately its author, the present very tall Headmaster, doesn’t need to stand on the shoulders of giants to see further. Whatever ups and downs the world of politics may continue to spew out, I expect there’ll be a good few more lads getting a fair start while he’s leading the way.

My thanks go to TV producer Paul Ryan for allowing me to create and publish stills from his film ‘One Day We Shall Remember’, and to MGS headmaster Mr Mark Tomkins for permitting me to reproduce photographs owned by the School.

My thanks go to TV producer Paul Ryan for allowing me to create and publish stills from his film ‘One Day We Shall Remember’, and to MGS headmaster Mr Mark Tomkins for permitting me to reproduce photographs owned by the School.

Footnote: The Sore Losers pulled off a hat-trick of wins in the annual OMS quiz on October 17th, 2018. Whether we’ll be allowed to keep the trophy as per time-honoured tradition is in the Committee’s hands; but we’ll certainly be calling it the Sore Losers Cup from now on.

Footnote: The Sore Losers pulled off a hat-trick of wins in the annual OMS quiz on October 17th, 2018. Whether we’ll be allowed to keep the trophy as per time-honoured tradition is in the Committee’s hands; but we’ll certainly be calling it the Sore Losers Cup from now on.